by Natalie Williams

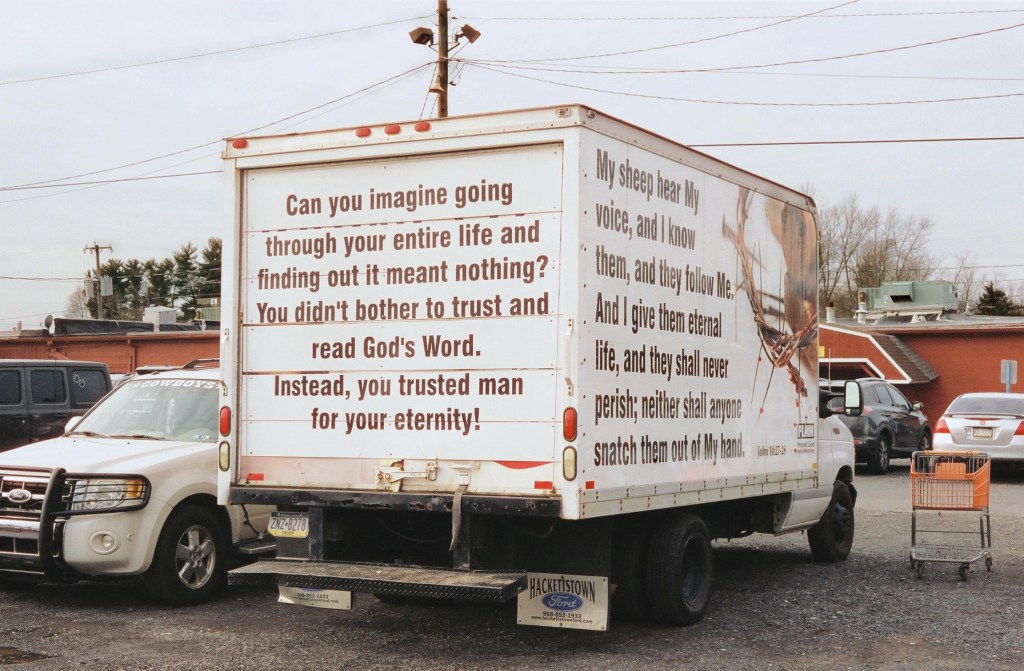

The language of Pennsylvania is mean, tough, and hard. Bumper stickers read “Rough Cunt”, trucks fly down the highway proudly waving the Confederate flag, and fathers hold their children while clad in shirts boasting “Cause of Death.” But within this semiotic landscape of the hyper-masculine, hyper-white, and hyper-”American”, toddlers and teenagers can be found swimming in a creek or waiting to jump into a pool on a hot summer day.

I imagine these children, teenagers, and adults are the same person photographed in different stages of their lives. The teenager jumping in the pool becomes the father holding a newborn baby, and a little girl waiting and staring at the ferris wheel could be my sister wading into the creek. This is how life is lived within Appalachia. Stories are witnessed and, often unconsciously, repeated through each following generation. Kids grow up watching daddy being mean and mommy being soft and are seldom given the chance to find their own pathway out of these narratives.

The severity of this dominating culture poisons the innocence, hope, and freedom of youth, culminating towards the moment where imagination becomes broken and generation cycles are refueled. The distinction between what is past and what is present is blurred as the questions of what once was and what could have been plague communal consciousness.

This series, named after the town of Ashland, Pennsylvania, investigates the intersection between industry and domesticity within Rust Belt America. These issues became amplified in Ashland when its sister town, Centralia, caught on fire due to an abandoned mine being turned into the town landfill in the 1960’s. Years after the fire first set ablaze, a young boy fell into a sinkhole and the town made national headlines. The state government declared eminent domain thirty years later and the former town was subsequently bulldozed. With tourists coming to view the rising smoke and bursting embers in the potholes of Centralia, Ashland stands in the wake of the environmental disaster just ten minutes away, now a blighted town. In this area of Pennsylvania, the creeks run acid orange and hillsides are stripped of their trees. The land seems irrevocably ruined.

Ashland explores how communities in Appalachian Pennsylvania are grappling with both the legacy and tragedy of industry, within their own personal lives and their communities. Towns like Ashland mythologize their history of industry yet are cursed by the irreversible physical impact on the land and the both willing and forced isolation of rural America. This series documents both my own coming of age story and, also, a larger look into how the landscape of rural Pennsylvania shapes one’s domestic and social experience.

The photographs piece together my personal narrative and a look into the lives of strangers, with these images all being taken within a seventy-mile radius of my hometown: Hellertown, Pennsylvania. In the image titled Norwood Street (Image 7), my sister swims in a creek where, two years earlier, a teenage boy fell victim to gun violence by his drug dealer and friend. My sister and I had frequented the park often that summer, staring into the abandoned green pool and watching people dirtbike throughout the swing sets, unaware of what had happened until we noticed a memorial on a light pole replete with teddy bears and decaying flowers. Though I had no personal connection to the boy, his story is not unusual. Kids trying too hard to be tough and get too close to the sun, spending their afternoons selling drugs or stealing their dad’s gun. Families torn apart by addiction, incarceration and death and the cycles that remain unbroken.

As a child, you live unaware of how class, race and gender impact yourself and others, or how systems of inequality create and uphold these differences. Lack of healthcare, opioid addiction, racial prejudice, and sexual violence are unquestioned and dominant. In fact, they are unrecognized as symptoms of a failing social ecosystem. The first step towards deconstructing these systems is acknowledgement, which Ashland aims to do. Norwood Street, for me, is this place of impact: where life and innocence was lost due to the pre-existing structures that make these cycles impossible to escape. One child was forced to grow up by shooting someone and one child was never given the chance to grow up at all.

My photos remember the history of the land and refuse to shy away from the politics of the region, illustrating the difficulty of growing up somewhere that feels unchanging and frozen. The personal is political, as every life is defined by the constraints and pressures of their surrounding landscape. I want to unpack these realities, without sanitizing or over-simplifying the region, as a way to deconstruct the narratives around rural America that shape collective memory and progress.

Ashland was shot on 35mm film and has been an ongoing project since June 2022.

Natalie Williams (b. 2001) is a photographer and collage artist from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Her photography work focuses on documenting rust belt Pennsylvania and the social spaces in this region that are both threatened by and defined by past industrial conquests. She currently lives in Los Angeles, California and holds a B.A. in Fine Art from the University of Southern California.