This is the second in a series of posts about labor violence in the anthracite coal region by Robert Schmidt. “Dynamite Bombings in Northeast PA, 1871-1957” was the first.

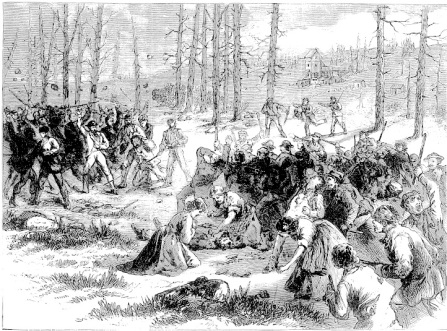

During the 1877 strike, Pennsylvania Governor John Hartranft ordered militiamen to the anthracite region after suppressing the riot in Pittsburgh. On their way to Scranton, militiamen were temporarily halted in Plymouth by strikers who had sabotaged the railroad tracks. This is a depiction of the violent conflict that ensued. Allan Pinkerton described the strikers in Plymouth as “more persistent and vituperative than at any other point within the State of Pennsylvania, save at Pittsburgh.” Citation: Allan Pinkerton, Strikers, Communists, Tramps and Detectives, p. 239.

To ask men to unite in self-sacrifice for principles, involving, as most strikes necessarily must, deprivation and distress to themselves and those dependent on them, and expect them to see their places filled without resentment that would kill the thing it hates, is to imagine men emancipated from the passion that sent Cain forth a fugitive on the face of the earth. A strike without violence of some sort is a barren ideality that exists only in the minds of self-deceived sentimentalists, professional agitators, and unsophisticated economists.

– Slason Thompson, 1904.[1]

by Robert Schmidt

Labor War and Oligopoly Formation

The postbellum industrialization of anthracite mining transformed Northeast Pennsylvania into a wellspring of labor militancy and launching pad for one of the first and largest trade union in the U.S. of its time. Established 1868, the Workingmen’s Benevolent Association (W.B.A.) coordinated an industry-wide strike the following year, negotiated the first collective bargaining agreement in mining, and won important legislative victories.[1] The W.B.A.’s success, however, triggered a concerted union-busting campaign that by 1875 led to its utter defeat. Over the twenty-year period between the W.B.A.’s collapse and the arrival of the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) in the mid-1890s, anthracite workers were largely unorganized. Even without union leadership, workers remained militant. Between 1881 and 1892, for example, there were more than 100 strikes across more than 100 mines—most of them wildcat and many of them successful in the short-term.[2]

Multiple failed attempts at coordinating a region-wide strike could not deter union organizers in their ambition to unify anthracite workers. From 1877 through the early 1890s, the region held firm as a stronghold of the Knights of Labor, a national organization that aimed to organize workers across trades led by Terrance Powderly, an area native and two-term Scranton Mayor. The Knights played a limited role the Great Strike of 1877, but they proved valiant (though unsuccessful) in its collaborative attempt in 1887-1888 with the Amalgamated Association of Miners and Mine Laborers to lead anthracite workers in a region-wide campaign.[3] However, it was not until the late 1890s that grassroots militancy, stoked by the Lattimer massacre of 1897, found a vehicle to region-wide trade unionization in the UWMA, which in 1902 led anthracite workers to what heretofore was the greatest labor victory in the U.S.[4]

In the late nineteenth century, Northeastern Pennsylvania was a forerunner of the labor movement and veritable microcosm of labor wars that were repeated in many parts of the U.S.[5] Anthracite workers pressed and challenged capital during the Civil War and over the decades that followed, erupting in labor war in 1863, 1869, 1871, 1875, 1877, 1887-1888, 1900, and 1902. Rather than a linear progression, the advancement of labor between the Civil War and the monumental strike of 1902 was a cycle of building and rebuilding: workers gained traction in the face of internal division and insurmountable opposition, only to collapse, rebuild, and press forward again. Neither did the success of anthracite workers follow a pattern that was spatially uniform. Rather, it unfolded unevenly across the region with interruptions of stalled momentum, disappointing failure, and violent (and sometimes self-defeating) conflicts.

Labor wars ultimately stemmed from the internal contradictions of industrial capitalism. Profit motives, the constraints of competition, and market gluts prompted wage reductions and other encroachments on the working-class, including cost-saving measures (which usually created unsafe working conditions), weight falsification, and the use of child labor. In response, workers pushed back against these encroachments and pursued higher wages, economic security, and a modicum of control over their working conditions. If collective bargaining failed, workers were inclined to use their most powerful weapon: the strike. Protracted strikes, in turn, led to the introduction of strikebreakers, which quickly antagonized anger and rage, leading in many instances to mob violence and sabotage of company property. Mine operators hired Allen Pinkerton’s spies to infiltrate worker meetings and the Coal and Iron Police to guard company property, and called in state and federal militias to suppress strikes and riotous activity. Leading up to the U.S. military occupation of Scranton, Wilkes-Barre, and Mauch Chunk during the Great Strike of 1877, Pennsylvania’s militia had already been ordered to the hard coal region on four different occasions to subdue upheaval. The period between 1903 to the 1922 bestowed economic stability and prosperity unto the region, but industrial peace proved far more elusive. From 1905 until the onset of World War II, the Pennsylvania constabulary (known locally as the ‘American Cossacks’) became something of a fixture in the region.[6]

If discontent was inevitable under the anthracite industry’s working conditions, the unionization of its workforce certainly was not. Battling on two fronts, union organizers were tasked with harnessing a workforce divided by ethnicity, culture, geography, and skill-level, only to face off against a concerted, well financed, and well-armed union-busting campaign.[7] The short-lived W.B.A. provides instruction in this regard. The W.B.A. proved that workers could collectively bargain with small, independent operators, but it was wholly overmatched by large operators, including Franklin Gowen’s Philadelphia and Reading Railroad (P&R) in Schuylkill County, and the combination of three large firms in control of the Scranton and Pittston area, that were hell-bent on suppressing workers and squeezing out small, independent operators.[8] Union-busting campaigns were reinforced, to a considerable extent, by regional disunity, ethnic divisions within the workforce, and deep economic depressions, which culminated to topple the W.B.A. in Scranton by 1871 and elsewhere after the Long Strike of 1875.

If unions agitated for higher wages, they also tempered the violent and self-defeating impulse of their rank-and-file. Unions were reluctant to call a strike, but they were adamantly against violence and destruction. After all, strikes were as disruptive to the worker as they were the operators, and violence undermined labor’s appeal to the community for support. Instead, unions championed collective bargaining and advocated for constructive ways to manage grievances and settle disputes. Absent collective bargaining and an institutional framework to absorb and direct discontent, however, workers resorted to independent action and, when triggered, were apt to a convulsive and violent response.[9] “Violence tends to appear where the workers are fighting a losing fight without it,” wrote Willard Atkins and Harold Lasswell, and when “the ordinary processes of collective negotiation are denied…. [workers may] decide that no other recourse exists than… guerrilla strikes.”[10] Decades of capital-labor conflicts escalated an arms race that led to a series of innovations. Capital broke strikes with the use of labor spies and private police, the state and federal militia, the blacklist, and the court injunction. In response to violent suppression, including mass shootings, the working-class introduced an innovation all their own, using dynamite to target strikebreakers and company property.

Over the last quarter of the nineteenth century, absentee investors secured a tight grip on the mining industry and truncated labor’s repeated attempts at unionization. Patterns of collective violence were the social cost of a tumultuous industry and the birth pangs of oligopoly formation that developed out of the actually-existing local conditions of class struggle: this violence was not “the preserve of one or another ethnic group or preindustrial culture,” but the expression of community solidarity that enforced a moral code that held “scabs” as an offender.[11] As one resident told an editor for Outlook in 1902, “The spirit of the group binds union men; for it they are willing to sacrifice, and according to its intensity so is their hostility against all antagonistic forces.”[12] Put simply, the cause of industrial conflicts rest not within some innate militancy of the working-class, but in the historical circumstances that set capital and labor in perpetual conflict: the industry’s exploitative conditions, danger, and the economic insecurity; the stubborn refusal of operators to recognize unions; and the use of strikebreakers.[13] The introduction of dynamite to labor war did not signal the radicalization the working-class (whether by anarchism or the Wobblies), but developed out of local conditions of class struggle that ushered along an arms race.

From the Draft Riots to the Lattimer Massacre: The Shifting Geography of Industrial Violence

In the annals of nineteenth century history, the U.S. is exceptional only for its industrial violence.[14] Before 1900, federal and state governments repeatedly backed capital in labor conflicts and escalated violence by providing militia support. As a major producer of steel and coal, Pennsylvania stood out among its peers as a landscape of recurring industrial conflict. For its size, in fact, the northeast corner of Pennsylvania rivaled Pittsburgh for its bloody disputes. The most serious labor disturbances during the Civil War were in the anthracite region, where a combination of labor militancy and resistance to conscription ultimately led to federal occupation, including military-subdivisions based in Scranton, Pottsville and Mauch Chunk.[15] Federal enforcement of the Conscription Act aided operators in the suppression of labor by construing strikes as organized resistance to the draft, which prompted militia interventions.[16] This set a pattern of occupation and violent suppression that endured well into the twentieth century.

After the war, Schuylkill County stood as the epicenter of Northeastern Pennsylvania violence through the Long Strike of 1875. The so-called Molly Maguires, a reputed conspiracy of insurgent Irish Catholic miners veiled behind the Ancient Order of Hibernian, allegedly perpetrated assaults and vengeful murders against mine bosses and company officials. The story has been the substance of local lore and a Hollywood film, but it has also sparked serious historiographical debate. The Molly Maguire conspiracy has been challenged and thoroughly debunked, but the myth was undoubtedly true in its consequence: ‘Molly Maguireism’ conflated violence and terror with all labor activism between the onset and the Civil War and the end of the Long Strike, and criminalized Irish-Catholics as its source.[17] The waves of violence attributed to Molly Maguires must be examined in the context of recurring industrial unrest. For the decades that followed, a pattern of industrial conflict similar to the Molly Maguire episode was repeated across various parts of the region and involved different ethnic groups—a strong indicator that industrial violence was not attributable to ethnicity or culture, but the product of local conditions.

The Molly Maguire hysteria was weaponized by the P&R’s concerted union-busting campaign. Leading a $4 million-dollar campaign to break the W.B.A., Gowen hired on the infamous Pinkerton spies to infiltrate W.B.A. meetings and the Coal and Iron Police, a publicly sanctioned but privately funded police force, to guard company property and escort strikebreakers.[18] With support from local newspapers, Gowen mobilized the Molly Maguire hysteria to sway public opinion against the trade union movement. Media representations ranged from unsubstantiated to exaggerated.[19] The Miner’s Journal, for example, repeated anti-Irish sentiments that branded workers as barbaric and beholden to an Old World tradition of violence.[20] In 1874, a letter from Mahanoy City to the New York Herald claimed that the power of the Mollies “is so great that law officials are seemingly powerless to effect their arrest and incarceration.”[21] John Morse, covering the Molly Maguire trials in 1877 for the American Law Review, described the region as “one vast Alsatia” (an esoteric reference to a land of lawlessness and debauchery in Thomas Shadwell’s The Squire of Alsatia) for its murders and other crimes.

Even after ten so-called Molly Maguires were convicted and hanged on a day the Philadelphia Ledger called “a day of deliverance from as awful a despotism of banded murderers as the world has ever seen in any wage,” the Mollies continued to be blamed for anonymous threatening letters and unsolved murders.[22] The Riot Committee investigating the anthracite region’s share of the 1877 strike averred that the Mollies were chased out of Schuylkill County into Scranton where they were accused of instigating violence.[23] Throughout the 1880s, the Knights of Labor were disparaged as a veiled Molly Maguire conspiracy.[24] The Molly Maguire narrative fizzled out completely by the 1890s as the Irish experienced a modicum of class mobility with the push of Southern and Eastern European immigrations. Anarchists and later communists supplanted the Molly Maguires.

The cover of F. P. Dewees’ The Molly Maguires: The Origin, Growth, and Character of the Organization exemplifies the sensationalism of the Molly Maguire narrative.

If some Irish Catholics ostensibly perpetrated murder and assault against mine managers, operators, government officials, strikebreakers, and others, their violence was not wholly inspired by ethnic heritage rooted in Ireland’s countryside. As Kevin Kenny cautioned his seminal study, Making Sense of the Molly Maguires, the region’s wave of violence occurred in response to immediate and specific historical conditions that require close examination. Kenny was unequivocal in dismissing the “gigantic conspiracy” hyped-up by contemporaries, calling it exaggerated and implausible.[25] For one, the Molly Maguire hysteria far exceeded a pattern of crime that a conspiracy could have possibly been responsible for. “Violence was endemic to the coal fields of the time,” wrote Ann Lane in her 1966 review of Molly Maguire historiography, and union-busters were successful in linking “the general violence of the period to the labor movement for the purpose of destroying it.”[26] Violence was also far too widespread throughout Northeastern Pennsylvania, including the burgeoning cities and towns of the northern field, to be attributable to the coordinated and criminal handiwork of Irish Catholics alone, much less an oath-bound organization that worked in secret and left no discernable evidence of their conspiracy. The crime-solving capacities of law enforcement were limited. There were law enforcement officials to police crime; the Coal and Iron Police were a publicly charged organization that focused narrowly on protecting company property. Dozens of murders in the 1860s and 1870s remained unsolved—e.g., in Schuylkill County alone there were 46 unsolved murders from 1863 to 1866—and the Molly Maguires (and Irishmen more broadly) conveniently served as the ‘usual suspects’.[27]

Irish immigrants represented a disproportionate share of a destitute and economically insecure working-class. As such, they were criminalized wholesale and assigned an ethno-culturally subordinate position within the division of labor and class stratum—a status that would soon be inherited by Southern and Eastern European immigrants. The violence perpetrated by the working-class must be examined in relationship to the criminalization of labor activity and the legal and extralegal violence that they were the victim of. In the case of the Irish in the 1870s, Sidney Lens agreed that they “engaged in violence, but they were as frequently the victims as victimizers.”[28] In fact, “there was much more terror waged against the Mollies than those illiterate Irishmen ever aroused.”[29] Indeed, Pinkerton spies, the Coal and Iron Police, and vigilante committees were tasked with targeting labor leaders and others active in the labor movement.[30] To be sure, there is no shortage of evidence that W.B.A. rank-and-file (of various ethnicities) engaged in violence, but the union itself did not encourage it. For whatever the W.B.A. may be faulted for, it went to great lengths to reign in the frustrations of the working-class and, at its height, was successful in doing so. There was an inverse relationship between unionization and violence: violence peaked in the years preceding the W.B.A., during the strike as the W.B.A. weakened, and over the months immediately after the union’s collapse.[31]

If the Molly Maguire narrative could provide Gowen and others the justification to suppress and criminalize the labor movement, it also obscured the power differential between capital and labor and the role violence had served for each. For labor, violence was a desperate, episodic, and last-ditch effort; for capital, it was state-sanctioned, organized, overwhelming, and most often the winning gambit. By reducing labor activism to criminality, union-busters could justify the asymmetrical violence that belay their dominance and dismiss the structural conditions that stoke the ambers of working-class militancy to begin with. Such widespread violence was not the doing of a coordinated secret society, but conditioned by protracted periods of economic insecurity, exploitation, and convulsive social change that rendered the working-class combustible, easily ignited to riot and violence by the spark of wage reductions, wage-theft, and the use of strike-breakers. To the extent that Molly Maguireism existed, it is best understood as a method of responsive violence, not a coherent secret society.

Broadening the geographical scope of analysis also challenges the narrative that Schuylkill County violence was transplanted from Ireland. The late nineteenth century was an epoch marked for violence across many rapidly industrializing regions of the U.S. Much like in the southern field, episodic violence had meanwhile swept the northern and middle fields from late 1874 through the middle of 1875. In the Scranton area, for example, where a suspension in early 1875 idled some 15,000 men, a Chicago Tribune correspondent reported that “distress, squalidness, and crime prevail at an alarming degree” where “not a day or night passes but what a burglary or highway-robbery is recorded, and frequently an unfortunate falls beneath the murder’s weapon.”[32] On a few occasions, the press blamed the Molly Maguires for unsolved crimes in Hazleton, Wilkes-Barre, Scranton, and accused them of conspiracy in Carbondale. In late 1874, for example, the Mollies were accused of igniting a powder keg in the basement of a mine manager from Hazleton, causing structural damage to his North Wyoming street property. In Scranton, they were accused of mob attacks, rape, and the murder of Michael Kearney, a miner whose body was found horribly mutilated at the bottom of an 80-foot embankment.[33] However, the Molly Maguire hysteria did not sweep the northern field as it did in Schuylkill County. Beyond speculation and rumors, there were no arrests and no evidence to substantiate that these crimes were committed by a conspiracy ring.

If Molly Maguireism was a truly a violent tradition transplanted from Ireland, then surely Scranton would have been a crucible of Irish-perpetrated terror.[34] Census records for 1870 and 1880 document not only more Irish-born immigrants, but also a greater share of their respective totals, in Luzerne County (and in Lackawanna County by 1880 after it formed out of Luzerne County two years before) than Schuylkill County. According to the 1870 census, Irish-born immigrants represented 23 percent of the total population (24,610 of 106,227) in Luzerne County, compared to 15 percent in Schuylkill County (12,465 of 85,572). In the 1880 census, Irish born represented only 10 percent of the population (10,836 of 103,826) in Schuylkill County, whereas for Lackawanna and Luzerne they were 20 percent (12,497 of 62,352) and 14 percent (13,598 of 97,349), respectively. [35] The northern field—and Scranton in particular—had all the important characteristics to antagonize a deep-seated Molly Maguire tradition of vendetta and guerilla war, including oppressive and unfair working conditions and a weak (and largely non-existent) union. Scranton boasted the third largest diaspora of Welshmen in the world, offering an abundant supply of likely victims: Welshmen occupied managerial roles, demonstrated a pattern of preferential treatment to their fellow countrymen, and subjected the Irish to violence and chronically exploitative working conditions. Furthermore, considering the fluid movement of workers throughout the region, it is conceivable that alleged conspirators rooted in Schuylkill County would have moved northward into Scranton and surrounding areas.[36] Benevolent societies, including a large and vibrant Ancient Order of Hibernian, flourished throughout the Scranton area. Furthermore, if Irish nationalism and sympathy for the Irish countryside might stoke a violent Molly Maguire tradition allegedly rooted there, then Scranton and rest of the northern field were well suited to nurture Irish-perpetrated terror. The anthracite region was site of some of the most active fundraisers of the Land League Fund through the Irish World in the early 1880s, but of the region’s 47 branches, 16 were in Lackawanna and 21 were in Luzerne, whereas only 4 were in Schuylkill.[37]

If the Molly Maguire narrative was particular to Schuylkill County, it was not because there were lower wages or more exploitative conditions there.[38] The Irish-born faced exploitative and oppressive conditions across the entire region. Rather, the geography of Molly Maguireism is best explained by Gowen and the Miners’ Journal’s led a campaign to criminalize the labor movement. In contrast to the northern field, where corporate capital had already secured its dominance over the workforce of the northern field by 1860 and swiftly toppled a unionization effort in in Scranton in 1871 (discussed below), mine operators did not need to weaponize an anti-Irish narrative to sustain its union-breaking campaign or criminalize the labor movement.[39]

In Northeastern Pennsylvania, the bitter antagonism between the Irish and Welsh was the only violence transplanted from Europe. To be sure, this Old-World conflict was replicated not because of some deep-seated and eternal hatred between the two groups. Instead, the anthracite industry reproduced an ethnically stratified labor regime nearly identical to those in the mining regions of South Wales.[40] Operators enjoyed ethnic division and compounded it by playing on it to their benefit.[41] Native protestants and Welshmen likewise enjoyed a position of privilege within the industry. In Scranton, it was not the Irish, but the Welsh who demonstrated a pattern of intimidation and violence in the workplace and community in the 1870s. Here, the Irish were used as strikebreakers and more likely to be victims of violence than perpetrators of it.

Ethnic cleavages undermined unionization efforts across the region, but in Scranton these cleavages were particularly acute. In January of 1871, a thirty percent wage reduction prompted Scranton’s W.B.A. to strike. Led by the Welsh, the strike was peaceful until Irish and German laborers, compelled by hunger, returned to work in early April.[42] As skilled-miners and chieftains of union, the Welsh were far better situated to absorb the strike’s cost in comparison to the low-skilled and lower paid laborer positions that the Irish and German filled. Suffering starvation for a cause that Welsh miners had far more to gain from, the Irish and German returned to work in early spring. In response, Welsh strikers used violence to intimidate strikebreakers and sabotaged company property to idle mining operations. On April 7, for example, hundreds of Welshmen marched “with drawn revolvers and muskets, defying the police and civil authorities,” to six mines to halt their operation.[43] Workers leaving the Tripp Park colliery for the day were ambushed with stones and clubs; three men were shot and killed and many more were stoned nearly to death.[44] A small militia tried to halt the mob but was overpowered and disarmed.[45] Many strikebreakers were attacked at their home—in one instance strikers shot a man in the leg they had mistaken for a “scab.” Strikers also used explosives to destroy the mouth of the Morris and Weed’s coal works and tore up nearby rail tracks and they set fire to the Nay Aug and Rockwell breakers.[46] It wasn’t until the governor ordered some 900 militiamen that the rioting was quelled.[47]

A month later, Welshmen raided a meeting of a few dozen laborers as they planned another return to work. The Scranton Republican, a paper otherwise favorable to the Welsh, was outraged to report that two dozen “frenzied Welsh females” led the charge as some thirty men followed, calling strike-breakers “blacklegs and every opprobrious epithet their filthy tongs could utter,” which ignited a riot.[48] The strike finally ended a week later, as the superintendent of the Lackawanna Iron and Coal Company (LI&C), William Walker Scranton (W.W. Scranton), reopened the Brigg’s shaft and escorted workers home with an armed militia. Met by a crowd of some two hundred Welshmen, W.W. Scranton and his militia were poised for a violent confrontation. Accounts of the conflict are discrepant, but one reports that a stone thrown by a striker provoked the militia to fire into the crowd, killing two Welshmen and wounding a few others.[49] The shooting ended the strike, but animosities between the Irish and Welsh led to the W.B.A.’s defeat and undermined unionization efforts for twenty years that followed.[50]

Meanwhile in the southern and middle fields, the W.B.A. coordinated with operators to limit output to thereby increase coal prices and raise wages. However, Gowen intervened by using freight rates to discipline operators into halting cooperation with the W.B.A. Gowen’s aim was twofold: 1.) end the coordination between

This image and the one above it are artist renditions of the Scranton strike of 1871 published in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated, April 29, 1871.

labor and operators that controlled output and prices and 2.) reverse the wage gains the W.B.A. achieved in 1869. Following Gowen’s direction, some operators resumed operation with strikebreakers, which, like in Scranton, sparked violence.[51] In Mount Carmel, for example, strikers surrounded a boardinghouse in early March around 1 a.m. and used explosives to destroy the property. When one of the strikebreakers, George Hoffman, woke up from the sound of an angry mob trying to break in and looked out the window, a gunman fired a shot through the window that ultimately killed him. As twenty-eight others fled the property to escape gunshots, the mob carried in a keg of powder, which they ignited with a long fuse, blowing the “gable end and side off, and entirely gutting the building.”[52] According to the Miners’ Journal, “their hellish design would have been accomplished only for the timely awakening of Mr. Hoffman, who only awoke for a moment to gaze out into the night upon his assassins, preparatory to closing his eyes in the last long sleep that knowns no waking.”[53] To make amends for what was likely the earliest documented case of bombing in the region, the W.B.A. disavowed this attack and offered a $500-dollar reward for bringing the culprits to justice.[54] Ultimately, Gowen was successful: the Schuylkill region’s strike ended in May and the strike of Lehigh workers ended the following month.[55]

The strike of 1871 was a mere dress rehearsal for the Long Strike of 1875, when some forty-thousand miners of the middle and southern fields held-out for more than five months. Gowen triggered a strike in November of 1874 by imposing a drastic and non-negotiable wage reduction.[56] His primary aim was not cost savings, but to break the W.B.A. stronghold of the southern field and continue asphyxiating independent operators.[57] Anticipating the strike, Gowen stockpiled coal near their markets to withstand a protracted suspension. Meanwhile, he unleashed Pinkerton spies to infiltrate the W.B.A. and hired Coal and Iron police to guard company property. Gowen had plenty reason to be guarded: the wage reduction coupled with his unwillingness to bargain was bound anger strikers. The first few months of strike had been largely peaceful, made up of parades and demonstrations, but it turned violent when collieries began operating with strikebreakers.

Unable to target their rage at Gowen, strikers of Schuylkill and parts of Northumberland counties attacked strikebreakers and destroyed company property. Local newspapers and company officials were much obliged to document (and sometimes embellish) the violence and destruction that occurred frequently during the strike. A committee investigating the Philadelphia and Reading provided an informative, though not exhaustive, account of the incidences of violence and property damage that occurred in the Schuylkill and Northumberland counties during the strike between December 13th of 1874 and July 15th of 1875.[58] The New York Times published this list of outrages along with a sample of threatening letters:

Sample of letters sent to scabs. See “List of Outrages in Schuylkill and Shamokin Regions 1874,” New York Times, 06 August 1875.

It was a mistake to dismiss anonymous letters as idle threats. Strikers were apt to follow through, assaulting non-striking miners and stoning or setting fire to their home. Strikers also sidetracked and destroyed trains and set fire to loaded cars and company buildings. During the spring and early summer, hundreds of striking miners marched throughout the southern and the middle fields to halt mines in operation. As colliers began to operate with a tickle or returning workers, strikers mobilized to intimidate and assault them, but were met with armed militiamen. Strikers marched to the homes of strikebreakers in the Wilkes-Barre area. In one case, they unloaded revolvers into a doll of a “scab” they hung in effigy.[59] According Francis Dewees’ contemporary account on violence at the Philadelphia and Reading, “The repairmen on the railroad were stopped from their work, train-hands were threatened, railroad-tracks obstructed and barricaded, engines and cars thrown off the tracks, cars unloaded, property stolen and destroyed, houses burned; mobs riotously assembled, took possession of engines and trains displayed firearms, and drove men from their work.”[60]

When the Coal and Iron police and local forces proved too small and ineffectual to handle the riots, local officials called on the governor to send militiamen. In Hazleton, where riots and dozens of assaults of strikebreakers were taking place, some 500 militiamen were ordered in April. A correspondent for the Philadelphia Inquirer reported the streets in Hazleton had a “warlike appearance… crowded with countrymen and uncouth mountaineers, and the sidewalks sprinkled with militia.”[61] At the height of the strike, an estimated 1,500 National Guardsmen occupied communities across Luzerne and Schuylkill counties.[62] An editorial from a Wilkes-Barre paper complained that the military had supplanted civil authority and decried the threat to liberty that occupation posed, writing, “This city has been lately too much like a military camp.”[63]

In April of 1875, the Chicago Tribune’s report on the strike titled “Civil War in Pennsylvania” perhaps exaggerated local conditions, claiming that “barbarism reigns” and that “civilization, law, and society have apparently ceased to exist,” but to call it a civil war was not inaccurate: from militia shootings and beatings of strikers to striker assaults on scabs, violence occurred with near impunity. The paper reported one feud between neighbors in Pittston over the strike had escalated to murder, but the perpetrator was not brought to justice: “No Sheriff dare seize him; no jury would venture to convict him; no Judge could safely sentence him in that mod-ridden country.” Sympathetic to labor and not beholden to mine operators, the Chicago Tribune held operators, not workers, as the ultimate source of the violence: “The coal-owners are largely responsible for the state of things. For a series of years they have treated their men like machines, have shown not the slightest interest in their welfare, have spent no cent of their great gains in bettering the condition of their work-people, have fomented strikes and formed lock-outs for the sake of gambling in coal in New York and Philadelphia…”[64]

A divided workforce would invariably succumb to the united pressure of operators. And where militia occupation could not batter workers into submission, the long-smoldering starvation of the population over the course of the strike certainly would. It was against the backdrop of “scenes of woes and want and uncomplaining suffering seldom surpassed,” as Andrew Roy explained, that violence and discontent festered. Thousands of families “rose in the morning to breakfast on a crust of bread and a glass of water, who did not know where a bite of dinner was to come from… But workingmen must work that they may eat, and must eat that they may work, while capital can wait.”[65] After exhausting their credit, savings, and foodstuffs, mineworkers begrudgingly returned to work for reduced wages in June. Absent union representation to harness their animosity and discontent, the merciless defeat of the strike ushered in a crime wave attributed to the Molly Maguires over the months that followed.[66]

The wave of violence that swept Northeastern Pennsylvania occurred less than two years later and was prompted by wage cuts and economic insecurity at the depths of economic depression in 1877. In July of that year, a month after ten so-called Molly Maguires were condemned to hanging, the great railroad strike that swept much of the country had set Northeastern Pennsylvania aflame “like tinder.”[67] Perhaps mild in comparison to Pittsburg, the violence in the hard coal region was considerable nonetheless. In late July, mineworkers in the Shamokin area went on strike and sabotaged a Philadelphia and Reading station until they were squashed by armed vigilantes that killed at least one person and wounded several others.[68] In Wilkes-Barre, mobs of striking miners attacked freight trains and damaged property. Elsewhere in Luzerne County, strikers halted mine operations in Hazleton, Kingston, Plymouth, and Nanticoke.[69] The epicenter of violence, however, centered in Scranton, a city that “rested on a complex powder keg of social injustice…[that] needed but a brief spark to light the fuse that had lain exposed for so long.”[70] On July 24th, the Lackawanna Coal and Rail Company, a ten percent wage reduction on top of a wage reduction a month earlier, triggered its 2,000 workers to strike and demanded a 35 percent increase. Meanwhile, the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western, which had reduced wages by fifteen percent, suspended six collieries and reduced twelve others to halftime the previous March, reduced wages again by another ten percent, prompting a strike.[71] The strike paralyzed rail traffic and, without rail to transport coal, disabled mining operations. Mineworkers did not let this opportunity to strike for higher wages pass.

Scranton’s general strike did not last long. At the end of July, the rail and iron workers returned to work. Meanwhile, mineworkers met to plot out whether to return to work or continue their strike for higher wages. Already frustrated with the return of DL&W and LI&C employees, the otherwise peaceful gathering of mineworkers had ignited to rage and upheaval by a provocative letter read aloud, allegedly written by W.W. Scranton, that threatened to “either have them working for thirty-five cents a day, or be buried in a culm pile.”[72] The mineworkers began marching to the DL&W and LI&C workshops to enforce a work stoppage.[73] As workers made their way to Lackawanna Avenue, city mayor Robert McKune, who played key role in negotiating the return of rail, iron, and mine pump workers to work a few days earlier and was braced for unrest in his city, directed the crowd to disburse. Anticipating a violent conflict, the local militia was poised at various points and ready to assemble to disperse the crowd.

Jacob Riis, a housing reformer and journalist, known most widely for his How the Other Half Lives, was front and center of this conflict to chronicle what he saw. Fleeing mounting labor trouble in Elmira, New York, Riis was unexpectedly sidelined in Scranton because of sabotaged rails.[74] After setting about to explore the downtown, Riis bore witness to a large crowd of strikers as they faced off with “a line of men with guns, some in their shirt-sleeves, some in office coats, some in dusters” who were blocking advance onto LI&C property. McKune, aiming to preempt the conflict that had engulfed Pittsburg, confronted the crowd head on, “haranguing the people, counselling them to go back to their homes quietly.”[75]

Unphased by McKune’s appeal, the crowd attacked him clubs and rocks and almost killed him, but for the intervention of a Catholic priest. The attack on McKune triggered militiamen to fire into the crowd. Armed with Winchester rifles and totaling some fifty in number, many of the militiamen were local businessmen and clerks and officials of LI&C with deep hostility to strikers.[76] Organized and armed by W.W. Scranton and instructed to be ready to shoot-to-kill, the militiamen did not hesitate to shoot into the crowd.[77] Riis recounted the horror and panic he experienced as shots were fired into the crowd indiscriminately: “A man beside me weltered in his blood. There was an instant’s dead silence, then the rushing of a thousand feet and wild cries of terror as the mob broke and fled. We ran with it. In all my life I never ran so fast… one might have played marbles on my coat-tails, they flew behind so.””[78]

If workers initiated the violence by attacking McKune, the militiamen were responsible for escalating it to a massacre. Hyman Kuritz commented: “It is difficult to see how bloodshed could have been avoided considering the swashbuckling, arrogant, and militaristic attitude of W. W. Scranton toward the workers of the city. At first sign of possible trouble he was all for leading the Citizen’s Corps out to stop the demonstration by force, melodramatically telling his men now to be afraid to ‘shoot to kill.’”[79] Estimates of the death toll vary and details of those injured are discrepant, but there were at least three killed and between twenty-five and fifty seriously injured.[80] This violence prompted the governor to order five thousand Pennsylvania National Guardsmen to occupy Scranton and other communities across the region.[81] The militia was not well received—their Scranton-bound train was met with an ambush of rocks in the Wilkes-Barre area and halted by sabotage to the rail line.[82] Workers might have sustained their strike for longer, had it not been for famine and impoverishment over the course of two-months of occupation. They returned to work mid-October and the occupation ended in early November.

In justifying the shooting deaths, the Riot Committee argued that Scranton would have been as violent as Pittsburg, they concluded, had it not been for the swift and overpowering occupation by local and federal militias. Nowhere else in Pennsylvania “was there a harder set of men than at Scranton and vicinity,” they reported, and the violence was instigated by the Molly Maguires who were “driven out of Schuylkill County, having gathered in and about the city, besides the scores of other hard cases who have been there for years.”[83] For as sure as they were that the Molly Maguires were to blame, the source of the violence was far more complex. Harold Aurand’s study on the anthracite region argued that violence erupted because workers were left without an institutional framework through which to express their grievances.[84] Aurand drew an important connection between the conflict of the northern and southern fields, arguing that W.W. Scranton and Gowen manipulated violence to their own ends. “The outbreak of violence is understandable only in terms of an institutional breakdown,” Aurand reasoned, and though Scranton’s 1877 riot and the Molly Maguire episode of 1875 appear “superficially poles apart,” they represent an “institutional vacuum” in which violence filled.[85]

Artist rendition of the assault of Mayor McKune published in Allan Pinkerton, Strikers Communists, Tramps and Detectives.

Labor wars like those in the anthracite region were repeated in other industrialized areas of the U.S. over the last quarter of the nineteenth century. The great railroad strike of 1877, the Haymarket bombing of 1886, the Homestead strike of 1892, the Pullman strike of 1893, and many other smaller episodes of industrial conflict were ultimately squashed by violence.[86] In Northeastern Pennsylvania, the violent suppression of workers had taken its toll, and with the help of blacklisting, labor spies, private police, mass shootings, military occupations, and rising anti-union sentiments, it did so with chilling effect. Between the end of the 1877 strike and the Lattimer massacre of 1897, unionization efforts in the hard coal region remained weak and ineffectual. There were dozens of strikes over this period, but most were wildcat, sustained only for a very short period, and involved no more than four collieries at a time. “The operators’ success in running the mines on a nonunion basis is further reflected,” Perry Blatz argued, “in that almost no strikes from 1881 to 1894 had union involvement, except for less than one third of these from 1885 to 1887.” [87] In fact, only 16 of 73 strikes between 1881 and 1887 were union-led. It was undoubtedly difficult to organize an effective strike when for most years of this period there were less than 200 days of work.

In late 1887, the Knights, which had established its power center in and around Scranton after 1877, and the Amalgamated, a reorganization of the former W.B.A. with its base of support in the middle field, had joined hands to coordinate a region-wide strike for higher wages, accurate weighing of coal cars, fair work assignments, and standardized hiring and firing practices. However, their effort was botched from the beginning. Mineworkers of the northern field were too weak and unorganized to sustain a strike. The strength of labor rested in the middle-field, where the last vestige of independent operators faced competition from larger firms and invariably shifted the of competition by squeezing workers even tighter. With support from the Knights, the Amalgamated, representing workers in and around Hazleton, Shenandoah and the Panther Valley, called a strike on September 10th and pressed for a fifteen percent raise. Some 20,000 men went on strike. Among them were a large share of Southern and Eastern European immigrants—a population that natives had deep distrust and union organizers did not expect support from. In the southern field, the Knights found the P&R, facing bankruptcy, willing to negotiate and make a temporary 8 percent increase in August of 1887, but joined the strike in January when the company reneged on its concessions and lowered wages.[88]

Operators in the middle-field refused to negotiate and were poised for a quick victory. They went on the offensive by importing scabs and denying strikers credit at the company store. They even tried evicting strikers who lived in company housing but were stalled by a court injunction. Many local businesses came to the rescue by extending credit and the Knights provided modest financial resources. Workers and their families relied on savings and mutual aid as they had during strikes in the past; some workers even trekked to colliers in operation in the northern and southern fields or pursued temporary employment outside the region entirely. And like strikes before, it remained largely peaceful until collieries began operating with strikebreakers.[89] All the usual intimidation and violence followed as a trickle of workers returned. One strikebreaker outside of Wilkes-Barre woke up one morning to find “a piece of black crepe and a dead cow hanging to the front door of his house.”[90] A P&R general manager testified that his workers “were threatened; they were met at night by bodies of men and told if they returned to work they would be shot. In many cases notices were sent to me, ordering them to keep away, and calling them scabs.”[91] One engineer received an anonymous letter with a picture of a coffin, skull, and crossbones with a caption that read, “This will be your fate. Drop that engine. Your doom is sealed you —-. A huckleberry like you running an engine! A warning!”[92] Physical assaults on strikebreakers were common—many of them were family affairs in which strikers’ wives and children participated. In Glen Carbon, for example, a large group of women led a charge against strikebreakers, yelling epithets and hurling bread at them.

The most violent episode occurred in early February at a Shenandoah colliery.[93] As some fifty workers left for the day, a crowd of some 800 Polish strikers began throwing rocks and harassing them. When the Coal and Iron policemen intervened to protect the workers, they too were assaulted and knocked to the ground, which in turn prompted two of them to fire into the crowd, seriously wounding at least six.[94] As one stone-throwing striker was arrested and taken into custody before a magistrate, a group of some five hundred followed. The mob began stones and demanding the police release their prisoner and “pulled off an iron railing and used it to beat down the door” of the magistrate’s office. “Judging appeasement healthier than valor,” the magistrate released the prisoner was released on bail. The two Coal and Iron Policemen who shot into the crowd were meanwhile arrested by local law enforcement and transported another magistrate’s office. Behind them followed an angry mob of Polish strikers until sheriff arrived with an armed posse.[95]

The 1887-1888 strike was utterly unsuccessful, but important none-the-less for what it revealed. Southern and Eastern Europeans were far more likely to support a strike than violate the trust of their neighbors by working during one. And like the Irish and Welsh before them, these immigrants might resort to violence if it meant deterring scabs and keeping an operation idled. Set apart other immigrant groups in the region, however, this new wave was of a size and scale that proved a force to be reckoned with. The anthracite workforce had tripled between 1870 and 1890 and Southern and Eastern European immigrants led the region’s population’s expansion. If they were only a small percent of the population in 1880, they represented over forty percent of the workforce twenty years later.[96] Despite their size, however, they were on the receiving end of xenophobia and nativism befitting of a minority group. It is remarkable that these immigrants supported the labor movement at all.[97]

And as workers fled the Knights and Amalgamated after the strike, the weak position labor created deepened a void that nativism and xenophobia filled. As Hirsh argued, “Immigrants were convenient scapegoats for a vanquished generation of industrial workers…Nativism provided an outlet for frustration, a way of feeling strength on the face of weakness and demoralization.”[98] Of course, it was not just native workers who held anti-immigrant views. In his 1903 survey of the social and cultural life in the anthracite region, Peter Roberts, a sociologist and local minister, depicted Eastern Europeans (“Slavics”) as a barbaric and uncivilized population, prone to excessive drinking and violence.[99] Henry Rood, writing for Century in 1898, likewise called them “superstitious and murderous” and claimed that they “do not hesitate to use dynamite if they desire to blow up the home of one whom they particularly hate.”[100] In another publication, Rood said they were, “Violent by nature, accustomed to drinking vile concoctions of alcoholic liquors which would drive ordinary men crazy, they added a very undesirable element to the population.”[101] He said it was a pity that the resource-rich anthracite region was overrun and “denationalized by the scum” of Europe.[102]

Southern and Eastern European immigrants were subject to all the usual persecution and violence reserved for bottom rung of an ethno-racialized class system. Examples of hate and animosity abound. In 1884, about 100 Hungarian workers recruited and lodged by the P&R were met by 75 native workers who stormed their boarding house late in the evening as they slept, firing six shots toward the workers to terrorize them and using stones and brickbats to destroy the property.[103] In 1894 a camp of Hungarian workers hired to lay track between Pittston and Fairview was bombed in what heretofore and remained the most heinous and malice-filled dynamiting in the region’s history. A portable shanty that housed 58 Hungarians was bombed in the middle of the night, killing four and seriously injuring a dozen more.[104] Frank Shafer, with the assistance of four men and two women, all African-American laborers living in a nearby boxcar, confessed to placing dynamite under all four corners of the boarding house. Successful in exploding only 25 of the 100 cartons of dynamite with a battery timer, they would have likely killed all of them had their plot not been botched by faulty execution. In his confession, Shafer admitted his aim was robbery, but he expressed malice against Hungarians, telling investigators: “We blowed up the Huns to get ‘em out of the country. They’re no good and they all ought to be blown out.”[105]

If the 1894 bombing was indicative of a xenophobic mood and demonstrated the utter disregard for the lives of immigrants, it was also a harbinger of the Lattimer Massacre of 1897. In August and September of 1897, lower Luzerne County was set to erupt by a hair-trigger. The Campbell Act, a tax placed on male aliens that was lobbied for by the UMWA to put the brakes on immigrants flooding the workforce, was a major source of frustration, as was an unpopular mine foreman, Gomer Jones, who instituted new rules that squeezed workers. In mid-August, workers set up a picket at the Honey Brook colliery to protest Jones’ policy for mule drivers that added two hours of work with no additional pay. Angered by their defiance of his order to return to work, Jones used a crowbar to attack a young boy and was himself overpowered by the crowd and nearly killed. Other small strikes ensued into early September in which immigrants armed with clubs and guns that shut down collieries.[106] The united front that immigrant workers held could only be broken by overwhelming force.[107] On September 10, following instruction from UMWA leadership to be peaceful, some 500 unarmed mine workers, most of them recent immigrants, began a seven-mile march from Harwood toward Lattimer, outside Hazleton, to encourage a work stoppage at the Pardee Company.[108] However, these marchers were met by a posse of 86-armed Luzerne county deputies, who unloaded point-blank into the crowd, killing 19 and seriously wounding more than thirty. The Lattimer massacre holds the dubious distinction as the bloodiest industrial conflict to that point in U.S. history and the deadliest mass shooting in the region’s history.

The deputies who perpetrated the massacre were brought up on charges, but none were convicted. The xenophobic commentary and reactionary sympathies for the sheriff deputies that virtually repeat sentiments about the Irish from the Miners’ Journal from decades earlier. For example, the matter-of-fact sympathies the Philadelphia Inquirer just days after the massacre was particularly illustrative of the xenophobic mood:

Unfortunately, there is in the coal regions a vast population of foreigners, dragged here from the slums of Europe, who cannot speak the English language, and who are, for the most part, lawless and ready to fight…The flooding of the mining regions with an ignorant foreign population has filled the dockets of the various courts with all sorts of trail cases. Crime has greatly increased, and the outlook is anything but reassuring. The events of the past few days offer another argument in favor of a more drastic immigration law. The coal companies are largely responsible for the crime…They have brought here swarms of ignorant people, oftentimes vicious.[109]

In a similar vein, Henry Rood said, “…the terrible affair at Lattimer… never would have occurred had not English-speaking labor agitators aroused the immigrants to a frenzy because of alleged “wrongs.” The ignorant, hulking Slovaks and Polacks, and the brawny, cunning Italians, who formed the mobs, would not have thought of [marching]… had it not been for politicians and agitators.”[110]

As the anthracite industry continued its move toward oligopoly, the prospect of region-wide unionization seemed unlikely. And if victory was possible, it was not immediately apparent that the latest wave of immigrants would be the driving force behind it.[111] However, two important developments had set the stage for success. First, the UMAW, needing to expand their union as much as anthracite workers needed representation, set their sights on organizing the anthracite industry, entering the field in the early 1890s and absorbing the Knights of Labor and what was left of the Amalgamated, and had made important inroads in forming a region-wide union. Second, as the 1887-1888 strike demonstrated, recent immigrants were not a detriment to organizing that native workers and UMAW organizers imagined, but a pillar of the labor movement, particularly after the 1897 massacre. Building homes and churches in the region, the new immigrants were firmly planted and poised to fight.[112] Redirecting ethnic and regional divisions toward unity, the UMWA leadership took grievances to operators and ultimately to the White House and Wall Street in the 1900 and 1902 strikes as the working-class waged a concerted battle on the ground. It was at this point that that the pendulum began to swing in favor of labor.

Landscape and Labor War: The Introduction of Dynamite and the 1900 and 1902 Strikes

Over the second half of the nineteenth century, anthracite workers saw a laggard industry beset by anarchic competition and chronic overproduction blossom into a vertically integrated oligopoly controlled and coordinated by a coalition of J.P. Morgan-led investors.[113] This syndicate of absentee investors consolidated anthracite mining and railroad interests through a systematic elimination of independent coal operators and a series of railroad bankruptcies and consolidations.[114] To be sure, a handful of independent operators managed to survive the century, but they stood as “islands in a sea of corporate enterprise.”[115] However, the formation of this anthracite-rail oligopoly was not a seamless process, but a tumultuous one beset by internal contradictions. As coal was extracted from the earth and profits flowed to New York and Philadelphia, profound social and environmental costs were externalized locally in the form of landscape degradation, economic insecurity, poverty, and conflict.

If labor wars were endemic to the rapid industrialization of the region, they were not challenges to the capitalist system as such. Nor were they led by anarchists or outside agitators. Instead, recurring conflict developed out of local conditions and represented class struggle over the allocation of surplus value. As workers fought for a greater share of the fruits of their labor, operators defended their prerogative to exploit workers, decimate and under-develop the landscape, and return profits to investors. The reproduction of the working-class—indeed, the reproduction of the capitalist system itself—depends on the former; the competitive constraints of the industry (i.e. what Karl Marx called “the coercive laws of competition”) demands the latter. Force may determine the outcome, but it cannot settle the underlying contradictions that structures conflict in the first place.

Nothing fails like success. As capital toppled labor and harnessed the industry’s self-destructive tendencies, a series of transformations within and external to the region shifted the balance of power to workers. Entering the anthracite region in 1894, the UMWA led workers to their first major victory in decades in 1900 and a historic victory in 1902. It was an emerging union that used its momentum and resources from its 1897 win in the bituminous fields to unite the workers of the hard coal fields of Pennsylvania. It united workers behind a pragmatic and tangible goal of higher and equitable pay and job security. Pure-and-simple unionism, as the conservative trade union ideology of the UMWA came to be known, was a depart from the republican critique of industrial society that had informed and directed worker militancy after the Civil War into the 1880s. Meanwhile, at federal level the sweep of progressive era politics had redefined the role of government in labor disputes, which set the stage for political intervention in the 1900 and 1902 strikes not as a strikebreaker, but as an arbiter.

Innovations in worker suppression evolved out of a quarter century of labor war. By the 1890s, capital could rely on a tactical ensemble to break strikes and squash militant organizing, including labor spies, private police, professional strike-breakers; the Pennsylvania National Guard; the blacklist; and the court injunction.[116] Mass shootings and other forms of asymmetrical violence—used most demonstrably in the Lattimer massacre—made it increasingly difficult for crowds to organize in demonstrations, pickets, and other mobilizations. And though capital could not suppress labor’s militant impulse, it did displace much of the conflict across time and space. Strikers were not at all deterred from intimidating and attacking strike-breakers, company foreman and superintendents, and Coal and Iron police, and they continued to sabotage company property as they had before. However, by the late 1890s they did so increasingly with a campaign of terror that introduced dynamite to the conflict. After Latimer, violence and sabotage that might otherwise occur in daylight by angry mobs of strikers gave way to midnight bombings carried out in secret. Put simply, mass shootings led workers to dynamite.

The way in which workers perpetrated a pattern of dynamite bombings, assault, intimidation, and sabotage cannot be dismissed as random, senseless acts of violence and destruction. Rather, this response developed inextricably to the provocations of militiamen, Coal and Iron Police, local sheriff deputies, and by 1905 the Pennsylvania constabulary that assaulted workers with clubs and shot their rifles into crowds with regularity. T.S. Adams, writing in 1906, explained that, “capital and labor have been playing the game of war for more than a century, and the game has been reduced to a science.”[117] The rules of engagement transitioned from “spontaneous outbursts… [that] was sporadic, passionate, defiant” to a sustained and systematic violence was cunning, coordinated, and institutionalized. He explained that “the real gravity of this systematic violence … is the state military preparedness which it connotes, the intensification of the conflict between labor and capital which it signifies, the armies of strike-breakers, spies and counter-spies whose existence it reveals.” Even the strike itself was becoming less a spontaneous (and often ill timed) reaction and more a coordinated attacked to assert maximum damage. As Shalloo so aptly commented, “If the nineteenth century may be characterized as ‘long violence,’ the first years of the twentieth century may be characterized as ‘decisive violence.’”[118]

The Northeastern Pennsylvania landscape was not passive, neutral ground, but a mediating factor that shaped the contours of labor war. Nature divided anthracite mining into separate fields, which allowed operators to play one field off against the other, much as they did one ethnicity against the other within fields.[119] Physical distance separated towns and cities across a 400 square mile area, and the barriers of culture and language further slowed communication between fields and dampened attempts at igniting an industry-wide strike.[120] Variegated work regimes and pay differences among collieries likewise frustrated union organizing. Before the formation of the anthracite oligopoly in the 1890s, the inter-regional competition among operators undermined the prospects of a region-wide strikes—a strike in the southern and middle anthracite fields increased demand and output elsewhere, allowing operators from the northern field to raid the market and raise wages and hold workers from joining a region-wide strike.[121] The industry as a whole kept an oversupply of collieries so that, as one operator described, “if a strike should occur at one point, the supply of coal could be kept up at another point.”[122]

Anthracite mining comprised a single-industry, but it operated across an uneven industrial landscape that was internally divided and set against itself. On one hand, King Coal dominated the region and provided its primary source of economic lifeblood. Workers were left with few employment alternatives not directly or indirectly tied to mining and its auxiliary industries, including rail, ironworks, and explosives. To maintain worker dependency and keep wages depressed, operators oversupplied the workforce by recruiting waves of destitute European labor. On the other hand, in creating a region that was decidedly working-class, King Coal set the conditions in which the working-class became self-consciously so. Workers relied on mutual aid and a dense economy of exchange, strengthened in large measure by community organizations and religious institutions, to endure low wages and chronic underemployment. In turn, the cohesiveness and resource mobilization that sustained and supported workers and their families during periods of insecurity and depression became the foundation upon which they could weather strikes and sustain union-breaking efforts.[123]

Strikes were family affairs—it was not at all unusual for mineworkers’ wives and children to participate in demonstrations and often led attacks on scabs. The importance of women to community solidarity and to solidifying the labor movement cannot be overstated. Their wages and homemaking, to say nothing of their resource mobilization and participation in strikes, allowed families to settle permanently. In fact, textiles, including silk, lace, and hosiery, gravitated to region in the 1880s, as did other low-wage, non-durable manufacturing over the decades that followed, because of its comparative advantage of cheap female labor: the wives and daughters of mineworkers desperate enough to work under sweated conditions.[124] Though wages were low, they were steady and provided a substantial source of household support, most crucially during slumps and strikes. Women also fulfilled a significant role in the informal economy. As operators of unlicensed saloons, boardinghouses, and bawdyhouses, for example, they provided important services to migratory, unmarried male workers in a region with an imbalanced sex ratio. Altogether, women reinforced the labor movement and played a crucial role in reproducing the chronically underemployed male workforce upon which the anthracite industry depended.[125]

The cities and towns of Northeastern Pennsylvania were not isolated company towns that could easily discipline the working-class.[126] On the contrary, anthracite communities were incubators of militancy.[127] Workers and their families made up nearly the entire population: the region lacked a middle and upper-class of corporate leaders and professionals that would typically be found in prototypical company towns. In fact, Gowen and W.W. Scranton, for all the power they wielded, were merely resident managers of businesses controlled by absentee investors.[128] Workers did not have to fear eviction during strikes because very few lived in company housing; and most purchased supplies through non-company owned establishments.[129] During strikes, public sentiment supported labor and held operators as the primary threat to social order. Workers also controlled local politics and public service positions, including the local police, magistrates and jurors, which established a check on corporate power, especially with regards to law enforcement in the 1900 and 1902 strikes.[130] As Edward Martin observed in 1877, anthracite communities have “the character of business and social centers, but the mining classes, being largely in the majority, regulate and control them.”[131]

Working-class solidarity made it difficult and costly for operators to suppress labor activism and break strikes. The Coal and Iron Police were an expensive necessity to guard property and escort strikebreakers.[132] In fact, the absence of law enforcement in some communities, and the utter lack of their cooperation in many others, led operators to lobby for state sanction to establish the Coal and Iron Police to begin with—the source of violent provocations and shootings. Men had to be imported from Philadelphia and elsewhere because it was difficult to recruit private police or raise a militia from among the very population they were ordered to suppress. In 1875, for example, the general for the Pennsylvania National Guard dismissed Pittston’s militia from duty because they were “composed almost entirely of miners, many of whom are strikers, and their sentiments leaned too favorably on the side of the labor element.”[133] The Iron Age complained, “The turbulent element of the mining population has long enjoyed immunity of restraint at the hands of the civil authorities, and, should a collision occur, we hope the troops will make the occasion memorable by a judicious distribution of cold lead among the rioters.”[134] In his 1878 address, Pennsylvania governor John Hartranft said that lawlessness was permitted by a citizenry disinclined to serve as militiamen. “The men who engage in these riots are voters and the tenure of the offices of those in authority depend in a large measure upon the god will of these turbulent electors,” he said. These communities had an “unhealthy moral public sentiment that in the event of a disturbance permits the officer to neglect his duty, refuses itself to uphold the law.”[135] Conscientious of the cost to occupy a community, Hartranft and other governors were reluctant to send in the Pennsylvania National Guard. The Guard was no panacea for labor unrest, however. Coal operators were frustrated with the Guard’s limited focus on keeping the peace and the fact only adjunct generals, not operators, could make direct orders.[136]

The restructuring of the U.S. economy after the Civil War reshaped the relationship between labor and capital and presented an insurmountable challenge to the republican ideology that workers held. Before the Civil War, industrialists and the working-class were embedded in everyday interactions.[137] Industrial disputes were settled primarily on a person-to-person basis. Workers believed they were not subordinate to capital, but coequal, and strikes were not meant to disrupt industry as much as put it back into balance. Mineworkers viewed themselves as skilled and semi-skilled workers with a high degree autonomy: they were not subject to strict discipline and managerial authority that would be typical in a factory setting under Taylorism.[138] In contrast to a factory worker’s routine tasks, mineworkers carved intricate underground mines and extracted hard coal from unique and complex geological formations.[139]

Workers believed wholeheartedly in America’s promise of equality under the law and believed it was a place set apart from its peers where class mobility, self-sufficiency, and even prosperity were ensured for those willing to work for it.[140] For all its fury, the labor movement was fighting for the ideals and promise of the American republic. However, instead of finding the political equality, economic stability, and independence, workers confronted enduring wage labor dependency and all the social inequities it entailed.[141] In response to the tumultuous and sweeping change ushered in by postbellum industrialization, workers developed a critique of industrial capitalism, evident in the Knights of Labor platform, which aimed for broad social, economic, and political transformation of American society. During the 1887-1888 strike, for example, the Knights urged American citizens to “rise up…to assert their independence, to restrain the monopoly tendencies of incorporated wealth, and to restrict the arrogant capitalistic element that is assuming ascendency in this country” that if let continue would “destroy our republican form of government.”[142] Scranton Times editor Aaron Chase displayed a similar antimonopoly worldview in his commentary during the depth of the 1877 strike on September 28th.

The trouble lies in the greed of the corporations, and their habit of dictating terms to laborers, dealing with them as if they were serfs if not machines, instead of treating them as reasonable beings with feelings, and a conscience as well as a stomach. Americans brought up on the Declaration of Independence instinctively rebel against this kind of tyranny. The corporation is an impersonality. It issues orders. It is not a mere question of wages between the corporations and their working people, but also and very largely a question of method of dealing. The workingmen insist on being treated like human beings. They demand that the human elements of reason and conscience and sympathy shall have a place in the relations between employer and employee. The law of supply and demand, which ignores the existence of brain and heart and even stomach may operate on commodities, but should not be allowed to sweep human beings into its remorseless and insatiable maw.

In 1897 strikers marched behind an American flag on their way to Lattimer where they were massacred by Sheriff deputies. It was not atypical to see workers march behind an American flag during a strike or other demonstration. Whether immigrant or native, workers in the labor movement understood their participation as a struggle to attain the promise and ideals of the American republic.

If workers were deeply resentful of the destabilizing impact of industrialization, they did not develop a radical, anti-capitalist ideology in response. Workers were class-conscious, but the vast majority of them did not aspire to the revolutionary change that Marx believed inevitable. Rather, the majority of anthracite workers fought not against capitalism as such, but against an emerging industrial order that depreciated their status. If Northeastern Pennsylvania’s labor wars were of a frequency and “of a kind that most Marxists had long believed would convert any proletariat to socialism”[143] then socialism was conspicuously absent. Part of the explanation rests in the fact that strong trade unionism was a prerequisite. In contrast to the strongholds of municipal socialism in Milwaukee, Wisconsin and Schenectady, New York where trade unionism was entrenched, anthracite mineworkers held only a tenuous grasp of trade unionism between the Civil War through 1888 and were overtaken by nativism and antiunionism in the 1890s. [144] Second, and more important, is the fact that socialism was crowded out by the political power that workers wielded at the local level. Ethnic machine politics, the growth of the public sector, and public spoils absorbed much of the working-class, particularly after the turn of the century, and affirmed the legitimacy of local political institutions.[145] As David Montgomery commented, “The capacity of America’s political structure to absorb talent from the working class was perhaps the most effective deterrent to the maturing of a revolutionary class consciousness among the nation’s workers during the turbulent social conflicts of the nineteenth century.”[146] Put simply, the growing public sector not only took actual and potential leaders away from the labor movement, but also repudiated the tenets of socialism, which rendered the working-class impervious to its seduction.

Absent radical ideology, what could have inspired workers to weaponize dynamite? Contrasting sharply with the Haymarket Affair and many other cases of dynamiting that reviewed national attention, the introduction of dynamite in the hard coal region did not stem from anarchist ideology. (To the extent that ideology played a role at all, there was a demonstrable correlation between the propensity of dynamiting and the entrenchment of the UMWA’s conservative trade unionism.) Nor were outside agitators to blame. Worker access to dynamite and the skillset to use it successfully were principal factors, yet not alone sufficient, to explain the timing and scale of its weaponization.[147] Dynamite was accessible for more than decade before it became weaponized: the anthracite industry began using it in large quantities for extraction by the early 1880s after its U.S. patent expired and important innovations made it a viable explosive. And yet, it was not until the turn of the century, some years after workers had already developed proper practices in handling, preparing, and executing it, that those skills were transferred to bombing properties.

Dynamite became a mundane part of the working-class experience across most of the U.S. over the last quarter of the nineteenth century. The anthracite region, in particular, was saturated with it. Local firms manufactured it; local merchants sold it; and it was easy to steal from work or purchase stolen at a low price. And with so many trained in its use, law enforcement found it difficult to narrow a suspect pool after a bombing. As Frank Nealis from the Scranton Republican said in 1929,

the percentage of the population that understands explosives is on about the same pro rata basis as automobile drivers. Most every male resident in this end of the state did his turn at some time or another… in the mines. They are learned how to set off explosives both blasting power and dynamite. Not only does every other man in this section understand the uses and abuse of dynamite but he understands fuses, squibs and the manner of control of blasting charges.[148]

Before the introduction of dynamite, the use of explosives in labor conflict was uncommon: dynamite was an explosive uniquely well suited for bombing and offered far more precision and destructive capacity than black powder. Bombings also required careful planning and execution, which did not accommodate the convulsive passions of a riotous mobs of the 1870s and 1880s. The foremost aim of strikers was to intimidate potential scabs and keep operations idle. In this regard, bombing was a less preferred method if face-to-face confrontation was a viable option, particularly if the aim was to persuade would-be scabs to join the cause. Furthermore, a narrow focus on ideology only obscures the broader arms race of labor war that mass shootings had escalated. Dynamite bombings were not at all a symptom of radicalism: they were a common and quite ordinary act of violence and destruction that occurred in a variety of contexts.[149] The key advantage of dynamite was that it permitted an individual to execute an attack without confrontation and therefore without the risk of being shot. Slow burning fuses and timers could make it easy to escape planting a bombing undetected.[150] The fact that bombings occurred across the region immediately after 1897 is instructive that the working-class used dynamite in response to asymmetrical violence that they were the target of. As Lattimer so spectacularly demonstrated, labor activism of all variety, violent or nonviolent, including worker marches, demonstrations, and other gathering of groups, were likely to prompt a violent result that ends with worker casualties. Non-union workers were likewise swept up in the arm-race as they began carrying firearms to defend attacks.

Minitab software generated 55 random months between 1890 and 1902. A Boolean search of “dynamite or dynamited or bomb or outrage” was used for each monthly sample from local newspapers, including the Scranton Republican, Wilkes-Barre Times Leader, Pittston Gazette, among others on Newspapers.com. False positives were disregarded and only those instances of dynamite bombings relating to labor conflict were documented. This sample does not include instances of criminal activity in which dynamite was used to blow up a bank’s safe or organized crime bombings.